Gender and Age Distinctions

Gender and age distinctions have long been an important marker of status in Tswana society. The former was exhibited in many ways: men and women sat apart at social gatherings; and some places, e.g. the kgotla 'council-place', were for men only. Sons were, and in some cases still are, preferred, and a woman who bore only daughters was often despised.

There was a division of labour, with specific tasks allotted to people of each sex. A Tswana woman is a perpetual minor who is subject to the authority of male guardians - her father, brother or maternal uncle until marriage; her husband or his father or brother.

Women were excluded from political assemblies and religious ceremonies. Age was also the basis for distinction. As with other Bantu-speakers, the Tswana had to respect and obey those older than themselves, calling them 'father' - rra or ntate - or 'mother' mme; breach of this rule was a penal offence. Respect for elders extended beyond one's kin to the whole community. Children were grouped by physical development: birth to 2 years 'masea'; 3 to 8 'banyana'; boys 'basemane' and girls 'basetsana' of 9 to 13; and from 14 until they were allocated to an age-set - magwane, majafela or maphatisi.

Boys in maphatisi used to wear special costumes and perform songs and dances at gatherings for their age-set, and had great freedom, especially in sexual matters. During this period, they spent much time at cattle-posts herding their father's livestock. The girls helped by fetching water, crushing and grinding maize, preparing food, sweeping the houses, and caring for younger children.

Regiment Initiation

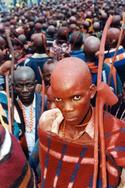

Allocation into an age-set or regiment 'mophato' marked transition into adulthood. A mophato consisted of men or women of roughly the same age who were initiated at the same time. Traditionally a regiment would be created by the chief every four to seven years, when eligible boys or girls, aged 6 to 20, were initiated together.

The mophato always included a member of the chief's family who henceforth was accepted as the leader. Many years ago the creation of a male regiment was accompanied by elaborate initiation ceremonies, known as bogwera. By the 1930s, however, the ceremonies had virtually disappeared, primarily because Christian missionaries regarded them as immoral and convinced 'progressive' chiefs to abandon and prohibit them.

A most conspicuous feature of bogwera was the circumcision and seclusion of male members of the new regiment in an isolated area in the veld. During their seclusion, initiates were subjected to hardships, graded in order of precedence and taught laws, traditions and customs. Girls were also initiated, in a ceremony 'bojale' held at home. It included dancing, masquerades and some form of operation - usually branding on the inner thigh. Female initiation also included severe punishments and other hardships, and formal instruction in matters concerning domestic and agricultural life, sex and behaviour towards men.

Each mophato was given a name by the chief at initiation, usually reflecting a contemporary incident, such as unusual rains or drought. The mophato retained that name from then onwards. A person was not considered an adult and was not allowed to marry until he or she belonged to a mophato. Members of a regiment worked and, in the case of men, fought together, but they were also intimate companions who were equals.

A sense of solidarity and regimental pride bound members: a particular sign of respect was to address a man by his regiment's name rather than his own. Members of a regiment were expected to respect all previously formed regiments and, in turn, could expect to be treated with deference by their juniors. Breaches of discipline in these and other matters associated with the regimental organization were dealt with by special ad hoc courts presided over by regimental leaders.

Ever-growing Revival

Despite efforts of Christian missionaries to end initiation early in the 20th century, there is today an ever-growing revival among the Tswana, as among others who long accepted that these teachings were not to be questioned.

Initiation has become a symbol of identity in two senses: people see themselves as Tswana by virtue of having been initiated by Tswana rites; more importantly, there is a strong sense across much of the subcontinent that undergoing initiation is a mark of African identity, and that young adults who fail to undergo some kind of initiation ritual are not 'real' Africans. The practices follow patterns similar to those used in the old days, but always with new features that make them very much a contemporary phenomenon, rather than relics.