The Marital Process

In traditional Tsonga society, choosing a partner was not straightforward, as the process followed a set of rules. First cousins could not marry; child betrothal was not practised, but a father might recommend girls to his son. A suitor commonly sent the woman a grass ring or thorn to indicate that he wanted to marry her. If the feeling was reciprocated, she would send him a grass ring or a thorn, confirming their relationship.

After the girl's father had formally expressed his approval of the match, the boy's father sent her family a cow, which sealed the agreement. Once this stage had been reached, further negotiations would be conducted through two intermediaries representing the families. Today working out the dowry due to the woman's family is still an important concern.

Tsonga marriage is more than a relationship between individuals. It cements relationships between families, carrying privileges and obligations that transcend the death of either spouse.

For example, should a wife die before producing a child, or should she be infertile, one of her relatives is supplied to bear children. When a husband dies, his relatives have to provide for his widow; if she is still fertile a younger brother might take her as a wife and produce children through her, on his deceased brother's behalf.

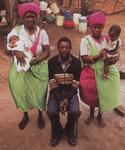

Traditional Ceremony

The traditional ceremony is still practised by many Tsonga. At the girl's departure from her home, a sacrifice is made, and she formally takes leave of her family and their ancestral spirits. This is followed by a 'handing over of the bride to her new family. After a marriage feast at the bridegroom's muti 'homestead', the couple is considered formally married.

Traditionally the bride had to follow well-defined rules of behaviour and etiquette in her new home. After her marriage she stayed in her mother-in-law's muti, helping her mother-in-law in her daily duties and in cooking the food. Her mother-in-law would instruct her in the customs of the family. She had to observe a range of rules of behaviour towards her father-in-law and his brothers.

She usually moved into her own muti after the birth of her first child but continued using her mother-in-law's cooking area until her husband's younger brother married. His wife then moved in with the mother-in-law. Once a young mother moved into her own home and had her own cooking area, she, her husband and their child formed a unit in the muti.

Initially, they stayed in the husband's father's homestead, but once the husband acquired other wives the establishment of his own muti became necessary. The usual practice was for the son either to build next to or extend his father's muti.

Over time this resulted in a lineage or even clan forming, as new generations added to settlements. Familial relations were strengthened through marriage since in subsequent marriages preference was shown for the younger sisters of the first wife.

A man's first wife might insist on his acquiring other wives as this enhanced her status in society and helped divide the workload of the muti between the wives and their children. This meant that the nuclear family developed into a functioning and economic unit, made up of different families, in which each individual had a specific status and responsibility for contributing to the common good.