Honoured for his Efforts

In 1984 Tutu won the Nobel Prize for Peace, becoming then the second South African to do so. He was honoured for his efforts to dismantle the oppressive rule in South Africa.

He made a public statement dedicating his Prize to the “little people” in South Africa and shared his prize money with his family, South African Church Council staff as well as a scholarship fund for South Africans in exile. The South African public had mixed reactions to his receipt of the award, some celebrating while others criticized.

The government itself remained silent about the event. He was later elected Bishop of Johannesburg and resigned as Patron of the United Democratic Front. He continued his work spreading the word of what was happening in South Africa, offering solutions along the way.

In the USA he and Dr. Allan Boesak met with Senator Edward Kennedy, inviting him to visit South Africa and addressed the United Nations Security Council as well as the Congressional Black Caucus, House of Representatives and the Senate. He continued to urge world leaders to pressure the South African government with economic sanctions.

Committed to Non-Violence

Tutu testified on the behalf of a captured cell of the armed anti-apartheid group, Umkhonto we Sizwe in 1984. He maintained that he was committed to nonviolence but could understand why black Africans under oppression would resort to using violence in their struggle for freedom. He called out the white government on their hypocrisy for praising armed liberation groups in Europe while condemning the same kinds of groups in South Africa.

Violence in the country continued to escalate and Tutu was asked to speak at many funerals. During his sermons, he continued to preach a message of nonviolence and was criticized by some for doing so who proclaimed that his modesty was an obstacle to liberation.

The African National Congress (ANC) called for citizens to make the country ungovernable, foreign investors increasingly withdrew their investment and in 1985 PW Botha declared a state of emergency in South Africa.

Through the chaos, Tutu remained hard at work. He led protests, supported the National Initiative for Reconciliation’s call for a nationwide strike to engage in a day of prayer and proposed a strike against apartheid. He addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York and met with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to press further for economic sanctions on South Africa.

Promoting Education and Sanctions

In 1985 the Bishop Tutu Scholarship Fund was formed. Its purpose was to provide scholarships to South Africans in exile. Tutu stood firmly behind the importance of an education.

At a conference organised by the Soweto Parents Crisis Committee, he warned of the dangers of an uneducated generation who would not have the skills necessary to occupy important positions in a post-apartheid South Africa.

In 1986 Tutu visited the United States again to urge sanctions. He also visited Japan, China and Jamaica for the same reason. Later that year he was elected Archbishop of Cape Town before becoming the president of the All Africa Conference of Churches.

Mediating Conflict

Tutu, along with other church leaders, became a mediator of conflict between protesters and police. They diffused tension in Alexandra Township in 1986 and at the funeral of Ashley Kriel in 1987 among other incidents.

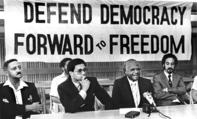

When the government banned 17 organisations in 1988, they organised a protest march, which was banned too. In response, they formed the Committee for the Defense of Democracy and when their rallies were banned they replaced it with a service at St George’s Cathedral.

Tutu took up the cause of the Sharpeville Six in 1988. The group had been sentenced to death and Tutu, opposing capital punishment, pressured PW Botha to spare their lives.

He met with Botha himself and the two clashed before Tutu was successful. The Sharpeville Six’ sentences were commuted. In response to Tutu’s defiance, the government orchestrated a campaign, distributing anti-Tutu flyers and stickers, paying protestors and even harassing his wife.

Even after apartheid was abolished, Archbishop Desmond Tutu knew that his work was far from over. He still had a dream for world peace and r...

Even after apartheid was abolished, Archbishop Desmond Tutu knew that his work was far from over. He still had a dream for world peace and r... In 1990 FW de Klerk announced the unbanning of political parties like the ANC and political prisoners were released, among them Nelson Mande...

In 1990 FW de Klerk announced the unbanning of political parties like the ANC and political prisoners were released, among them Nelson Mande...