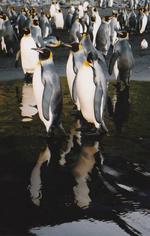

Uncertain Future

The penguins of Marion Island face an uncertain future. The ocean currents around Marion ebb and flow to their own unfathomable rhythm. South of this area, around the Antarctic continent, is the Antarctic Polar Frontal Zone. North is the Sub-Tropical Convergence. Both are massively powerful oceanographic fronts. Running between them, and directly in the path of Marion, is the weaker Sub-Antarctic Front.

It seems that the ocean immediately around the Prince Edward Islands swings between a two-phase system. In some years strong currents push between the two islands, bringing with them organisms from the deep ocean. This makes excellent feeding for the flying birds such as the petrels and albatrosses, which can reach the offshore food. When the system switches to the second phase, the currents do not push between the islands. All the nutrients that are washed out from the penguin and seal colonies accumulate close to the shore instead of being taken out to sea, bringing about massive algal blooms.

Near-shore feeders - the penguins that swim for their food - relish in an orgy of feasting. But the algal blooms along the coastline of Marion are on the decline. The Sub-Antarctic Front has shifted south relative to the islands by as much as 1.5 degrees since 1974, making way for warmer waters from the north. The temperature of the ocean in the vicinity of the island has crept up steadily by 1.4°C over the last fifty years of records, in parallel with the 1.5°C increase of Marion's mean temperature.

The fate of the rockhopper in these parts depends on where this trend is headed. A massive 94 per cent decline in rockhoppers has been recorded at Campbell Islands near New Zealand since the 1940s. While the study that reported this decline omitted over-fishing as a possible factor, it did state the decline was associated with rises in sea surface temperatures and reductions in the penguin's fish source.

Trend or Temporary Anomaly?

Conservation ecologist at Stellenbosch University, Professor Steven Chown, has researched the islands for years and says the question remains whether this is an ongoing trend or a temporary anomaly. 'Will the Sub-Antarctic Front end up on Antarctica's shores? That seems a bit unlikely because the Antarctic Polar Frontal Zone has been stable there for the past thirty million years,' comments Chown. 'But the other question is whether there's been a regime shift. So instead of this linear trend of continuous warming, who knows where it's going to end? We may have seen a shift from one system to another, which may be about to stabilise. We don't have enough data to know for sure. We haven't recorded for long enough to know whether that's happened.'

Symptom for Change

The changes that have taken place on Marion are symptomatic of a broader problem - of a planet that is becoming 'a big corporate world that is homogenous from north to south, from east to west, dominated by a few weedy feral species,' comments McGeoch. 'We are such a widespread species, with a highly effective transport and communication system, that we are introducing the same species all over the world. Eventually we are going to be living in a homogenous environment.'

Do we want this, McGeoch asks, or do we want to 'live on a planet that is diverse, where every part looks unique and operates differently, where a variety of species are interesting and look different'?

Chown explains it like this: you wouldn't want a single, homogenous system for the same reason that wise investors would never plough all their capital into one policy because, if it folds, they are history. For the planet to absorb changes, we are going to need a bit of variety. Biodiversity is the blueprint of the future, whatever that turns out to be. Allowing species to die is like plundering your savings.

In medical terms alone, nature provided the world with nearly $200 billion worth of pharmaceuticals in 2002 - half the global expenditure for health cures in that year. Biological diversity is described as the sum total of 1.75 million species of plants, animals and micro-organisms (and the many more not yet discovered), as well as the systems in which they struggle with one another in search of their own individual niche in the greater scheme of things.

This vast wealth, which has been banked away during billions of years worth of evolutionary process, allows the human species to continue sifting through nature's secret and prolific stash to find cures for their prevailing physical and psychological ills. And this is just a fraction of the greater number of goods and services that nature provides us with daily. 'That's the economic reason,' Chown states. 'The philosophical reason is straightforward. Are you supposed to look after things or just kill everything?'

It's not a question you can resolve easily, he comments. Every person may have a different opinion on this but there is no doubt that people are really short-sighted if they think they can live without the biosphere around them. Where would they find their food? Destroying the biosphere, Chown says, is the equivalent of going out and just shooting every species you see - simple as that.