Sample Bead Card

But after English money was introduced into the region in 1829, local communities began to demand payment in coins, which was used to purchase items such as clothing, hoes and tin pots.

Following the introduction of a cash economy, the use of sample bead cards containing glass beads of different shapes, sizes and colours played an important role in marketing beads to merchants and wholesalers for resale to trading stores in outlying rural areas.

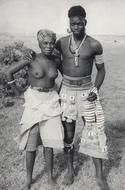

For the Love of Men

It is not clear how the status of these women was affected by the growing availability of beads in the Eastern Cape after the 1830s, but from this period onwards beads began to form part of the gifts exchanged between the families of brides and their grooms.

Throughout much of the 20th century, young women also took pride in making beaded items for their future husbands.

Gendered Labour

Entering what is still viewed in some places as a female profession, they commonly learn to make beadwork, guided by their professional mentors in this as in all the other arts associated with divination, such as the ability to identify the cause of ailments and to mediate between the living and the dead.

In recent years, some male members of the Ibandla lamaNazaretha, or independent Shembe church, have also begun to make beadwork for sale to other members of the Church, effectively challenging historically entrenched divisions of labour.