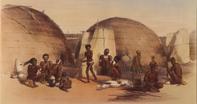

Commenting on this scene, which he recorded in the Umlazi district close to Durban in 1847, the artist, George Angas, drew attention to a man ‘engaged in carving a wooden milk-bowl, partly secured in the ground’.

In a comparatively early account of the process of the making of such vessels, Wood wrote in The Natural History of Man (1870): ‘In hollowing out the interior of the pail, the (carver) employs a rather ingenious device.

Instead of holding it between his knees, as he does when shaping and ornamenting the exterior, he digs a hole in the ground, and buries the pail as far as the two projecting ears. He then has both his hands at liberty and can use more force than if he were obliged to trust to the comparatively slight hold afforded by the knees’.

Historically, indigenous carvers lacked access to the labour-saving tools that are commonly used today. In the absence of handy contraptions such as vices, they resorted to digging holes in the ground to secure logs of wood.

Alternatively, they gripped unfinished carvings between their feet, relying on additional props to help steady bowls and other items while working on them. In the past, the tools used to fashion these household utensils varied substantially. Examples include small knives to carve large items such as chairs, long handled gouges and, quite commonly, also spears.

Bowls like these are still being made to this day. In Limpopo Province carvers generally used hardwoods to produce household utensils, including bowls, which are now also sold to external markets.

Spears were often used in the production of carved household objects in combination with other utensils such as axes, adzes and knives. The skilled blacksmiths who forged tools like these also made hoes, piercing irons, digging-rods and bifurcated or two-pronged iron rods for picking up lumps of meat.

Although commonly used as carving utensils, assegais were forged for the regiments of chiefs and kings competing for control over land and long distance trade relations. Along with oval shields, they were the favourite trophies brought back to England by soldiers returning from the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. For this reason, they have survived in considerable numbers to this day.

In recent decades, the tools used by rural carvers have included a host of items acquired either from local trading stores or hardware suppliers in near-by towns such as axes, saws, chisels, hand planes and drills.

Even so, skilled artisans often rely on makeshift utensils such as motor-car springs, tools fashioned from pieces of metal sawn from the railings of bridges passing over local streams and rivers, and discarded scraps salvaged from abandoned farm implements.