Early 19th century Hide and glass beads Height 44.5 cm; Width: 15 cm Aprons like these, worn by young Tswana female initiates, were recorded by European explorers as early as the 1870s.

These aprons covered the buttocks, and were tied to the initiates’ waists with a leather strap. The beads, which at that time would have been very expensive, were stitched directly onto the leather apron.

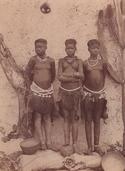

Young Ntwane Girls, Probably Early 20th Century

This photograph depicts three pubescent girls wearing beadwork similar to that associated with the Pedi and their Ntwane neighbours, who settled at Kwarrieslaagte in present-day Mpumalanga province in 1903, thus ending a period of repeated migration during which their dress and other forms of adornment were influenced by a number of North Sotho groups.

Because the hairstyles of these girls are consistent with those adopted to this day by young Ntwane initiates, the photograph was probably taken just before they entered the initiation lodge, or on their return from this period of seclusion, which is associated with instruction in the sexual and domestic roles women are expected to fulfill once they get married.

Lovedu Beaded Apron

Limpopo Province Late 20th century In recent years, the beaded aprons worn by Lovedu initiates have all been characterized by an extraordinarily abundant incorporation of discarded plastic trinkets such as broken watches, birdcage mirrors, plastic medicine spoons, cheap costume jewellery, and other recycled items.

Richly colourful, they sparkle against in the light and jingle to the rhythm of the wearer’s body. Combined with cheap, locally-manufactured plastic beads, items like these attest to the inventive creativity of communities where the cost of purchasing imported glass beads has become too prohibitive.

Limpopo Province Late 20th century Given both their remarkable quality of excess and the eclectic materials from which they are made, the beaded aprons produced by Lovedu initiates in recent years bear comparison with the glitz and glamour of famous designers like Versace, whose fashion items were described on one occasion as “following Oscar Wilde’s dictum that nothing succeeds like excess”, on another, as combining “beauty with vulgarity”.

Prior to his untimely death in July 1997 Versace produced clothing that was overtly opulent and loudly eye-catching, not unlike the aprons of Lovedu initiates, which actively challenge traditional notions of tastefulness.

By Professor Sandra Klopper