Culture: Zulu Period: 19th century Material: wood Left: H 13 cm, L 43 cm Right: H 14.5 cm, L 37 cm The amasumpa (raised 'warts' or bumps) pattern on these two examples originated in the Zulu Kingdom in the nineteenth century where the motif was considered to represent wealth in the form of cattle.

It was relatively uncommon for the central leg of headrests of this kind to differ from those at either end. Variations like these attest to the inventive powers of skilled carvers, some of whom introduced interesting departures from the standard amasumpa design.

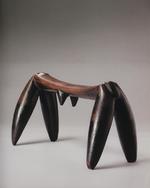

Culture: Zulu Period: 19th century Material: wood Height: 16.5 cm, Length: 30.5 cm Obvious allusions to cattle through tail-like extensions at either end and horn-like legs are fairly common in headrests from the Southeast African region.

These details served to affirm the role many Southern African communities ascribed to cattle in mediating relations between the living and the dead. Since the ancestors were also responsible for regulating the fertility, not only of cattle but also of their own human descendants, the addition to this neckrest of breast-like projections heightens the powerful allusion to sexual potency or fecundity evidenced in the expressive treatment of the forms.

Culture: possibly Swazi Period: 19th century Material: wood Height: 14 cm, Length: 42.5 cm Headrests of this kind have been attributed to the Swazi on the basis of the vertical fluting used on the legs, but fluting of this kind was fairly common among other groups in the region.

The Swazi, who formed a coherent identity only relatively late in the 19th century, commonly incorporated symbolic allusions to cattle in their headrests, including tails at either end, and a central lug on the underside of its platform.

Culture: Tsonga Period: 19th century Material: wood Height: 16 5 cm, Length: 20 cm The economic and symbolic importance of cattle explains the use of a variety of cattle motifs and metaphorical allusions on headrests from the Southern African region. But cattle are only occasionally fully represented in figurative form, as is the case in this headrest.

This quadruped is unambiguously identifiable as bovine by its pronounced horns, although the breadth of the head and the stocky proportions could be seen as referring, if not to a buffalo, then specifically to a bull.

Because the control of cattle rested firmly within the male domain, it seems reasonable to postulate that headrests with this kind of iconography would have been used by men, and possibly by men of high status.

Culture: Tsonga Period: 19th century Material: wood Height: 15 cm, Length: 18.5 cm Some headrests combine human and animal features into a single caryatid, like the example in this image, where a human head with a headring completes an animal body.

The gendering of this image is visible not only in the hairstyle of the human head, but also in the detailed male genitalia of the body. Adze marks are clearly visible on the face and other areas of the headrest. This evidence of the carver’s hand animates the form, as does the addition of pokerwork details.

Culture: Ngoni Period: 19th century Height: 9.5 cm, Length: 44 cm The Ngoni people who live in Malawi and Tanzania are the descendants of a group who migrated from the area around present-day Swaziland to their current homes in the early nineteenth century.

Once they had settled, they adopted many cultural traits from their new neighbours, but they also maintained past customs linked to manhood, such as the use of the head-ring, age-grade regiments and an emphasis on cattle in their economy.

This bovine-style headrest can be traced back to its Zulu-Swazi origins, particularly in the use of horn-like legs and head/tail forms at either end of a low-slung yet elegant platform. The reference to cattle is as strong as that in some Swazi and Zulu examples, but these forms are nevertheless immediately recognisable as Ngoni.

By Professor Sandra Klopper