Beautiful rolling green hills, tropical palm trees, frequent cattle in the road, laughing children waving with both hands - these are my fond and eclectic memories of Swaziland.

I'd been there on holiday as a child and returned many years later for the opening of the revamped Swaziland Royal Swazi Sun International Spa. The roads had potholes, the buildings were somewhat derelict but the inhabitants were some of the friendliest, most hospitable people I have ever come across. The weekend at The Royal Swazi Spa was, needless to say, heaps of hedonistic fun.

Culture and History

But back to Swaziland itself. It is a country rich in culture and steeped in fascinating history. According to tradition, the original followers of the present Dlamini royal house of the Swazi nation migrated south before the 16th century to what is now Mozambique. As result of a series of skirmishes with locals, the Ngwane (as they then called themselves), settled in northern Zululand in about 1750.But pursued by a growing Zulu strength, the Ngwane had to move north in the 1810s and 1820s. Under King Sobhuza I, they established themselves in the heartland of modern Swaziland, conquering and incorporating many long-established independent chiefdoms, whose descendants also make up much of the modern Swazi nation.Contact with the British came early in Mswati's reign, when he asked British authorities in South Africa for assistance against Zulu raids into Swaziland. It also was during Mswati's reign that the first white Transvaal Boers settled in the country. Following Mswati's death, the Swazis reached agreements with British and South African Republic authorities over a range of issues, including independence, claims on resources by Europeans, administrative authority and security, though the white parties later reneged on those agreements.As result of Swazi royal protest, the South African Republic, with British concurrence, established partial colonial rule over the Swaziland from 1894 to 1899, when they withdrew their administration with the start of the Anglo-Boer War. In 1902 British forces entered the territory, proclaiming British overrule and jurisdiction in 1903, initially as part of the Transvaal. In 1906 Swaziland was separated administratively when the Transvaal Colony was granted the responsibility of government.Throughout the colonial period from 1906 to 1968, Swaziland was governed by a resident commissioner who ruled according to decrees issued by the British High Commissioner for South Africa. Under pressure from royal non-cooperation, this proclamation was revised in 1952 to grant the Swazi paramount chief a degree of autonomy unprecedented in British colonial indirect rule in Africa.In 1921, after more than 20 years of regency headed by Queen Regent Labotsibeni, Sobhuza II became Ngenyama (lion) or head of the Swazi nation. In the early years of colonial rule, the British expected that Swaziland would eventually be incorporated into South Africa. After World War II, however, South Africa's intensification of racial discrimination induced the United Kingdom to prepare Swaziland for independence.Political activity intensified in the early 1960s. In 1966, the UK Government agreed to discuss a new constitution. A constitutional committee agreed on a constitutional monarchy for Swaziland, with self-government to follow parliamentary elections in 1967. Swaziland became independent on September 6, 1968.In 1988 and 1989, an underground political party, the People's United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO) criticized the king and his government, calling for 'democratic reforms'. In response to this political threat and to growing popular calls for greater accountability within government, the king and the prime minister initiated an ongoing national debate on the constitutional and political future of Swaziland. This debate produced a handful of political reforms, approved by the king, including direct and indirect voting, in the 1993 national elections.Arts and Crafts

Says Nokwazi Mabila, Product Development Executive at STH: "I guess all crafts started many generations ago when our ancestors carved, weaved or moulded whatever utensil they needed, such that all craft in that time was purely for utilitarian purposes. These skills were passed from one generation to the next through a family apprenticeship system. Materials used must've been natural inputs readily available within those communities.""Its development however is another story. Trade and intermarriages between communities have played a major role in the exchange of skills and designs. This involved not only its function but size and finishes became a priority. I would venture to say that our forefathers at this point had alternatives. So not only function, but form became important." She goes on to say that the invention of money also meant skills were traded and the client's wants and needs took priority over historical function."Today we use these once utilitarian objects as decoration and objects of art. Interestingly enough, in my day-to-day dealings, I'm still confronted by the same question: what takes priority? Our traditions or market demands?"

She says that three skills still dominate the crafts industry in Swaziland today: weaving, pottery and carving.In weaving two grasses are normally used; lutindzi (a seasonal mountain grass) and baskets dominate this trade. "Women also weave the most beautiful baskets from sisal fibre," she adds. Mats in all sizes and baskets, for every use are produced. One type of basket work is so closely woven it will store liquids, the basket itself absorbing some of the fluid and keeping the contents cool by evaporation.Also manufactured are wooden sculpture, painstaking soapstone carvings, glassware, mohair, tapestries, imaginative pottery and silk-screened batik's and clothing present an array of colours, textures and designs.Nokwazi says the most buyers are from South Africa regionally and from Germany internationally. Swazi craft is available not only in Swaziland but South Africa with SA being the largest importer of Swazi craft in the region. "We usually ship our merchandise through DHL or inter freight internationally."The industry is dominated by women with most men carving only (women also carve). "Of note is that most of these crafters are old with little skills transfer to the younger generation so it would almost look like a dying skill, and this is something we are trying to rectify through training programmes." Despite this, Swazi crafts are hardly promoted in schools and the only influence that students get is from their mothers and grandparents who still actively work with craft.She is confident though that the industry can one day function independently in its own right. "Personally, I would like to the see the day when the craft sector is no longer a by-product of cultural activity nor a value add to tourism attractions but an economic sector that has a complete production and supply value chain."She says that in the handicraft industry, unlike in other industry, the crafter who is at the bottom of the chain makes the least. "Sometimes by the time that piece reaches the final consumer at R500 the crafter will have made R50 so it would appear that the middle man benefits the most." She says she's not sure how other projects are funded but at inception, STH was jointly funded by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. "We've been partly funded by agencies like the Commonwealth Secretariat, Technoserve and The United Nations.In terms of proliferation, artists and craftsmen are found in every corner of the country. The road through Ezulwini has, however, become the centre of the Swazi craft industry with numerous outlets and small markets on either side of the road. The Manzini Market and emerging outlets on the road to Siteki and Lavumisa are some of the other venues to choose from.There is much room for expansion in the handcraft sector, particularly for the players in the informal category. As mentioned, these are mainly self-employed women, who often possess little business knowledge and are hampered by lack of contacts, relying on passing trade and tourists who buy from roadside stalls and small shops. Further, due to lack of training, their goods may not meet international market requirements and, in any case, they cannot individually produce sufficient quantities to interest bulk buyers.In addition the STH, there are organisations such as Tintsaba Craft in northern Swaziland which have taken the initiative by employing rural women who work at home producing items such as traditional baskets. They are supplied with materials, thus eliminating the need to invest their much-needed cash, and also receive the training that ensures the goods they produce meet international standards. Collectively, these women can produce sufficient quantities to meet the needs of international buyers, with whom their mentors deal. Hopefully, in time, the industry will take its rightful place in the economy with any trace of exploitation eradicated.

By Jo Kromberg

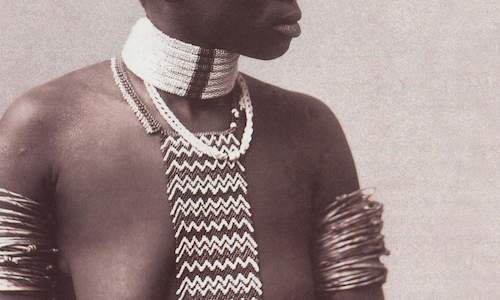

It was only in the second half of the nineteenth century that public collections of African art began to be amassed in response to the emerg...

It was only in the second half of the nineteenth century that public collections of African art began to be amassed in response to the emerg... It is commonly assumed that African beadwork traditions emerged through trans-continental trade relations that led to the importation of gla...

It is commonly assumed that African beadwork traditions emerged through trans-continental trade relations that led to the importation of gla...