Making of Musical Instruments

Arts and Crafts in Rural South Africa

The practice of carving artefacts associated with rituals is common throughout Africa.

Although the drums and other musical instruments used on these occasions are invariably made by men, in female initiation ceremonies they are always played by women.

In Twana and other rural communities, older women presiding over the initiation of young girls act as mentors and instructors. Throughout the initiation period, important activities are marked by beating drums and, in some cases, blowing horns or bugles.

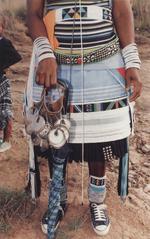

In most cases, the portability of drums is made possible by the addition of thongs strung around the back of the wearer’s neck. Unusually, some drums have handles probably inspired by the example of carrier bags and suitcases.

The drums used by diviners often vary considerably in size and shape. This is because, in some contexts, apprentice diviners are required to carve their own drums.

The carved drums played at events like weddings and the coming-out ceremonies of diviners vary considerably in size and shape. But the cured skin membranes stretched across their tops are always secured with the aid of large wooden pegs.

Large paint tins are sometimes turned into drums, but these tins are also used to carry water from distant rivers, and to store staple dry foods like sugar and maize meal, especially where people do not have access to the clay containers produced by rural potters.

Traditionalists today commonly make musical instruments from recycled materials like cans and bottle tops to create various kinds of percussive sounds. Items like these are more readily available than the seed pods formerly used for this purpose.

The use of locally manufactured musical instruments remains common. Many of these instruments are fashioned from animal horns, reeds and, more recently, brass pipes.

In the course of the 19th century, Moravian and other missionaries established brass bands to accompany congregants singing hymns at church services and on other religious occasions. Discarded instruments from these congregations have acquired new homes and functions in traditionalist rural communities.

The use of commercially produced brass horns and trumpets has become so widespread among rural traditionalists that outsiders sometimes form the impression that these communities no longer treasure long-established practices, including the production of indigenous art forms.

Although it is true that many of these practices have been eroded, for example through the impact of migrant labour, traditionalists still value the skills of local craftsmen and -women.

By Professor Sandra Klopper