Virtuoso carvings of spherical to pear-shaped wooden vessels like this one are often lidded. All have ridged or fluted surfaces. Some examples also have handles and tripod feet, while others are encircled by heavy outer armatures carved from the same block of wood.

None shows any sign of use. In the past, many of these vessels were attributed to the Swazi, but recent research has confirmed that they were produced in the Colony of Natal, appearing on colonial exhibitions in London (1862 and 1882) and Paris (1867) before entering various private and public collections.

At the 1862 exhibition in London, some of these virtuoso carvings were attributed to a man who was identified at the time as Unobadula. Today, this highly accomplished carver’s name would probably be rendered as unguNobhadule, i.e. he is Nobhadule.

Storage vessels like these ones have come on the market since the 1970s. Some were acquired before the 1850s, but most appear to have arrived in Europe from the 1860s onwards. Identical examples are recorded as having been on display at the Great Exhibition in London in 1862. Their shape is unlike any similarly-sized indigenously used vessels.

They usually have rounded bottoms similar to those found on clay pots nestled between stones when cooking food on open fires, which helps to explain the addition of legs.

Because the finely engraved ridged or fluted interlaced patterns found on these large pots are virtually identical to those associated with similarly shaped miniature snuff-boxes, it has been suggested erroneously that they were used as storage jars for tobacco. There is no field evidence pointing to this as an accurate reflection of their function.

Dr Robert Mann who was Superintendent for Education in the Colony of Natal for seven of the nine years of lived there (1857 to 1868) also served as the commissioner for Natal for the Great International exhibition of 1862.

Mann and some of his successors collected artefacts produced by communities living close to urban areas such as Durban and Pietermaritzburg, showcasing them as examples of the skilful craftsmanship of the indigenous inhabitants of the Colony.

The items they made for these exhibitions included headrests, spoons, shields, spears and large vessels, some of which were inspired by the intricately carved decorations associated with snuff containers.

This bowl is similar in style to figurative works that have been attributed to Muhlati, who lived in present-day Maputho in the early 20th century. According to Junod (1927), Muhlati claimed that he was ‘able to carve anything and everything: birds, four-footed beasts, or men. He was famous throughout the land for his talent’.

The shape of the bowl seems to have been inspired by that of a coiled clay pot but with the addition of a flaring circular base. The bodies of the two figures have been darkened through pokerwork details to suggest that they are wearing shoes, trousers, and shirts or jackets.

Because the two men look in opposite directions, there is no obvious front or back to bowl, which they raise on elongated forearms and support against their heads.

Muhlati, who produced unusual figurative bowls, once carved a sculpture of a leopard devouring an Englishman.

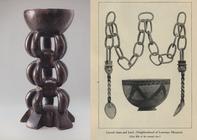

The production of virtuoso works for both local and external consumers became increasingly common in the late 19th century not only in southern Africa but also in other parts of the continent. Standing on an irregularly shaped five legged base, the bowl of this robustly-proportioned carving is supported by three registers of bulbous ascending loops.

The outer surface of the bowl has diamond-shaped patterning scorched in outline, while the inner surface exhibits signs of wear and use. Junod (1927) documented the use of diamond-shaped pokerwork patterning on other carved vessels from present-day southern Mozambique, in addition to spoons joined through looped chains fashioned from a single block of wood.