Emerging Interest in Figurative Arts

Before the 1980s, researchers working on the ritual arts of Africa commonly assumed that there was little if any evidence of figuration among the rural communities of South Africa.

This was partly because it was only in the course of the 1970s that scholars began to map the arts associated with local initiation and other ritual practices, and the prestige items commissioned by indigenous leaders and other dignitaries before and even after white settler communities assumed control of what in 1910 became the Union of South Africa.

Recent scholarly efforts to document the figurative arts of local communities have benefitted from early publications such as Muller and Snelleman’s Industrie des Cafres du Sud-Est de L’Afrique (c.1892) and Stayt’s The Bavenda (1931).

Free-standing Initiation Figures

In the past, some South African communities used wooden figures as didactic tools in initiation ceremonies that in the case of male initiates is associated to this day with circumcision rites.

Mock circumcision also forms part of some female rites, for example among South Sotho communities living in both Lesotho and the Free State.

Carved figures, which were commonly found in male initiation practices among the Venda, the Tsonga and various North Sotho groups, were also used in the female rites of Venda and Chopi communities. Among some groups, figures like these were burnt after the conclusion of the initiation process; but others reused these figures, which were lodged at the capitals of chiefs for safekeeping.

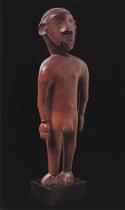

Pedi / Ntwane Initiation Figure

The Ntwane originally lived in present-day Botswana, but they became closely associated with the Pedi after 1903, when they moved to their present location in South Africa's Mpumalanga province following a series of relocations that probably began in the late eighteenth century. Today, these two groups share various traditions of dress and numerous ritual practices.

Both communities also have long-standing woodcarving traditions linked to male initiation schools. The didactic function of these initiation carvings is evidenced by the fact that they commonly depict paired male and female figures with prominently displayed genitalia.

This particular example, which is characterized by a remarkable balance between youthful innocence and modesty, on the one hand, and mature sensuality on the other, depicts a nubile female initiate wearing a miniature version of the front apron (makgabi) given to girls towards the end of their seclusion in the initiation lodge.

In addition to other accessories, like her hairstyle, which resembles the tlopo traditionally worn by brides and widows, this apron signifies the initiate's new status as someone who has been educated to fulfil the role of an adult woman.

The tlopo, which consists of a mixture of clay and animal fat rubbed into the head and shaped into a helmet-like structure, appears to have strong associations with notions of fertility and therefore with the continuity of the group.

Figurines like these were often destroyed at the end of the initiation period. Even so, there are considerable variations in the style of surviving examples historically classified as Pedi/Ntwane.

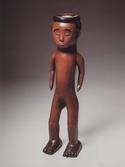

Tsonga Initiation Figures

Probably late 19th century Material: Wood Height: 47 cm Like several other South African groups, some Tsonga-speaking communities used paired male and female figures as didactic tools in male initiation contexts. Originally, all surviving Tsonga figures wore salempore cloths to cover their genitals, and many of the male figures also had head rings.

The latter practice stemmed from the fact that the ruling elite of the Tsonga, in particular, those who moved into the former Transvaal province following the defeat of Gungunyane by the Portuguese, claimed Zulu origin and therefore retained elements of dress and regimental structures similar to those developed by the first Zulu king, Shaka, and his immediate predecessors.

There is evidence to suggest that it was only among Tsonga-speaking communities from South Africa, rather than Mozambique, that these didactic carvings became associated with initiation practices. Influenced by their North Sotho neighbours, these communities appear to have used carvings like those originally associated with the Pedi and Ntwane to instruct initiates inappropriate social and sexual behaviour.

The surface of this work is characterized by the shallow adze marks typically found on some Tsonga carvings.

Probably late 19th century Material: Wood Height: 45 cm Tsonga-speaking communities, sometimes referred to as the Shangaan or the Tonga, occupy land in both Mozambique and South Africa, but it was only those living in South Africa that appear to have used sculpted figures for instruction purposes in male initiation rites.

Most, but not all, of these figures have explicitly carved genitalia, and many wear head rings, a practice adopted in emulation of the Zulu. In the past, it was assumed, incorrectly, that Tsonga initiation figures with head rings were of Zulu manufacture even though Zulu-speaking communities abandoned initiation practices in favour or regimental structures in the lead up to the emergence of the Zulu kingdom.

During the reign of the first Zulu king, Shaka, and his 19th century successors, head rings were sewn onto the hair of men when they got married.

As members of regiments (amabutho, sing. ibutho), these men continued to pay allegiance to their ibutho, but unlike the unmarried members of younger regiments who served as labourers and hunting parties in times of peace, married men were only required to assemble for national ceremonies and as reserves at times of war. Head rings were made from fibre and the gum of the mimosa tree.

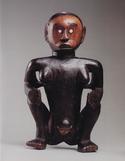

Probably late 19th century Material: Wood Height: 30 cm Despite the fact that some Tsonga initiation figures are said to have been collected in Mozambique, documentary evidence suggests that they were used by communities living in what was the then Northern Transvaal, where Tsonga youths entered initiation schools similar to those found among their North Sotho neighbours.

Because figurative sculpture from the South-east African region was often burnt at the end of the initiation period, surviving examples are comparatively rare, and it is seldom possible to attribute several works to a single artist. Even so, several sub-styles have been identified, and some are clearly by particular artists who appear to have carved figures for a number of initiation lodges.

Like some other figures, this one has very sturdy feet, voluptuous breasts and a chunky body, but the treatment of the pubic area is comparatively rudimentary.

Other surviving examples with elongated bodies, thin arms and pokerwork details, have very clearly delineated genitalia. In the case of the male figures, this includes the depiction of penis covers known among the Zulu as amancwado, (sing. umncwado), that were made from gourds or woven fibre.

Initiation Figure, Possibly Venda

Probably 19th century Material: Wood Height: 41cm Very few carvings produced by African communities depict pregnant women, and images of childbirth are especially rare.

Some examples from the Cameroon grasslands that show heavily pregnant women are associated with societies tasked to treat infertility, while the Chokwe (DRC and Angola) included scenes of childbirth and other domestic and ceremonial activities on the rungs of European-style chairs reserved for chiefs.

There are also a few graphic examples of childbirth among the Yoruba of Nigeria, which may have been intended as didactic tools. This carving, which depicts a woman crouching in childbirth, probably had a male companion. Works of this kind played an important role in exposing young initiates to the realities of life and death, and to the importance of appropriate social and sexual behaviour.

By Professor Sandra Klopper