When the artist-explorer George Angas published his folio volume on his visit to southern Africa, most of the hand-tinted plates of Zulu subjects included prominently displayed coiled baskets. The majority of these vessels were decorated with simple, over-sewn geometric patterns that are used to this day.

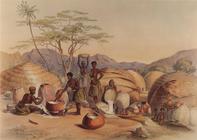

Unfortunately, early observers like Angas seldom recorded the source of the vegetable dyes for these decorations, but particular shades or colours appear to have been obtained from a variety of plants, usually by boiling or simmering the leaves, stems, bark, or branches. Angas’ plate depicting women making beer in a homestead near the Thukela River, formerly the border between the Zulu kingdom and the Colony of Natal, includes several large grain storage baskets along with baskets used in the production of home-brewed beer.

In the accompanying text, Angas gave the following description of this common domestic activity: “The large earthen jars over the fire contain the beer which, after boiling, is set aside for some days to ferment. One woman is stirring the millet about with a calabash spoon, whilst another is testing its quality in a little cup; a third woman is advancing with a basket of millet on her head, and a fourth is pouring out the liquor in waterproof baskets.”

The practice among neighbouring southern African communities of exchanging both basketwork technologies and various commodities can be seen in Muller and Snelleman’s observation that a basket from the Delagoa Bay region illustrated in Industrie des Cafres du Sud-Est de L’Afrique was fashioned in the “Zoulou” style.

The wide opening of this lidded basket suggests that it was made to meet a demand for containers from Portuguese traders who first settled at Delagoa Bay in the eighteenth century. The reference to the Zulu presumably alluded to the coiling technique used in the production of this basket.

Either way, Muller and Snelleman’s comment points to the complexity of trade relations among communities in the region, which in many cases was shaped by social and political inequalities sustained through the extraction of tribute, in the form of both raw materials and manufactured items like baskets.

By Professor Sandra Klopper